The Impact of Climate Risk On the Banking Industry

Insights SRD/New York Research CenterClimate change presents a serious threat to the financial stability of both foreign and domestic banks. The threats facing these financial institutions can be bracketed into three risk categories:

Physical Risks

Physical risks relate to the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events and longer-term shifts in climate, which cause physical damage to the value of financial assets as well as collateral held by banks[1].

Transition Risks

A transition risk is the climate risk resulting from mitigation challenges as societies decarbonize[2]. To stimulate a low- carbon transition, governments will need to take actions which will naturally impact the economics of borrowers. A transition risk example would be associated to GHG emission reduction policies such as carbon taxation, constraints on consumption[3]. Another example is risk arising from policies aimed at changes in land-use and farming practices.

Liability Risks

Liability risks come from people or businesses seeking compensation for losses they may have suffered from the physical or transition risks outlined above[4]. Liability cases could also include people who have suffered from physical events, such as flooding, making claims against polluting companies who they argue are, at least in part, responsible[5].

Banks are adjusting their strategies to safeguard against these risks.

On October 6, 2020, JPMorgan Chase announced plans to adopt a financing commitment that is aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement (“Paris”)[6]. As part of its strategy, JPMorgan declared its intention to help clients navigate the challenges and capitalize on the long-term economic and environmental benefits of transitioning to a low-carbon world.

In 2020, Bank of China Hong Kong launched the first RMB corporate green time deposit product certified by a third party in Hong Kong, and Bank of China London began assessing and managing the climate risk of its financial business.

Despite these voluntary actions by major international banks, climate risk stress testing is expanding at a rapid rate. Several jurisdictions have already announced climate-related stress tests and many others are considering following suit. The chart below illustrates noteworthy actions taken by regulatory agencies in a variety of jurisdictions as of March 2021.

The tests listed above will not evaluate capital adequacy, but may lead companies to look more closely at whether they need to hold more capital to cover potential losses from climate-change risks[7].

Conspicuous by its absence is the United States. As of now, banks in the U.S. are not subject to any climate related stress testing. This is not to say that the U.S. is ignoring climate risk. For now, U.S. regulators are focused primarily on measuring the problem and gathering data. This however, will likely change relatively soon. In July, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said the U.S. central bank is considering using climate stress scenarios to make banks more aware of and resilient to ever-more-frequent severe weather events[8].

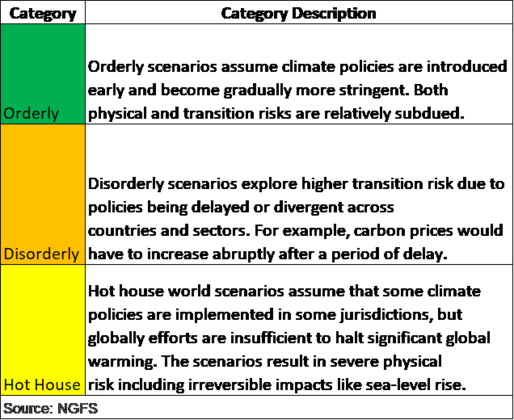

To date, regulatory agencies who are imposing climate related stress tests are drawing on scenarios published by the Network for Greening the Financial System (“NGFS”), which are backed by scientific research[9]. To cover a broad range of physical and transition risks, the NGFS designed the three following categories of climate risk scenarios:

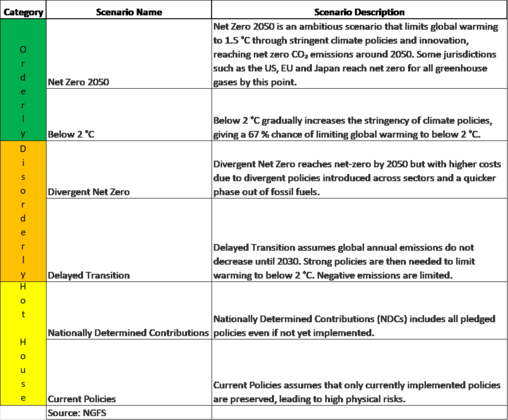

Within each category, the NGFS also designed two climate risk scenarios. The chart below categorizes and describes each of those scenarios.

Most regulatory agencies that are imposing climate risk stress tests only chose to base their examination on a few of the aforementioned scenarios.

For example, The Bank of England (BoE) published full details of its Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) stress test and guidance for participants on June 8, 2021. The purpose of BoE’s examination is to gain a better understanding of the vulnerabilities faced by banks and insurers under different policy and climate conditions. BoE elected to base their exam off one scenario from each category listed on the chart above: ‘Net Zero 2050’; ‘Delayed Transition’ and ‘Current Policies’. BoE also included additional risk transmission channels and supplementary variables as a basis for analysis.

It is also important to note that the scope of each examination varies based on the requirements of the presiding regulatory agency. In the case of the examination imposed by BoE, only the largest U.K. banks and insurers are required to participate[10]. For banks, BoE is focused on the credit risk associated with the banking book, with an emphasis on detailed analysis of risks to large corporate counterparties. For insurers, the CBES is focused on changes in Invested Assets (and Reinsurance Recoverables) and Insurance Liabilities (including accepted Reinsurance)[11]. This examination also explores how the participating firms intend to adjust their business models over time, in light of climate changes.

BoE will not use the results of this exam to set capital requirements, and individual participants’ projected losses will not be tied directly to actions participants are required to take. Instead, participants’ submissions may inform the Financial Policy Committee’s (FPC’s) approach to system-wide policy issues; the Prudential Regulation Authority’s (PRA’s) approach to supervisory policy; and guide further work between participants and supervisors to address any issues highlighted[12].

BoE expects to publish the results of the examination in May 2022.

The impact of climate risk on the banking industry has become more apparent in the past few years. While many banks appear to be taking action, they may need to increase the pace of their response. A PRA survey found that while a majority of banks have begun addressing climate risks as financial risks, those which they anticipate tend to be pushed beyond their typical four-year planning horizon[13]. Regulatory agency-imposed climate stress tests should expedite those efforts. However, climate stress testing remains in its infancy because measuring banks’ exposure to global climate change is considerably more complicated than assessing other hypothetical shocks they are subject to. Going forward, it will be critical for these testing practices and banks’ adherence to climate risk safeguarding measures to improve because the long-term safety and soundness of the industry may depend on it.

Disclaimer

Bank of China U.S.A. does not provide legal, tax, or accounting advice. This article is for information and illustrative purpose only. It is not and should not be regarded as “investment advice” or as a “recommendation” regarding a course of action, including without limitation as those terms are used in any applicable law or regulation. Bank of China USA does not express any opinion whatsoever as to any strategies, products or any other information presented in this article. This article is subject to change without notice. You should consult your advisors with respect to these areas and the article presented herein. You may not rely on the article contained herein. Bank of China USA shall not have any liability for any damages of any kind whatsoever relating to this article. No part of this article may be reproduced in any manner, in whole or in part, without written permission of Bank of China USA.

[1] Mazars_Financial_Risk_Climate_Change.pdf

[2] Financial risks stemming from climate change: “Challenging the degree of resilience into a constantly changing environment” (deloitte.com)

[3] Financial risks stemming from climate change: “Challenging the degree of resilience into a constantly changing environment” (deloitte.com)

[4] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/knowledgebank/climate-change-what-are-the-risks-to-financial-stability

[5] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/knowledgebank/climate-change-what-are-the-risks-to-financial-stability

[6] The Paris Agreement aims to hold the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and ideally, to 1.5 degrees Celsius – which would require the world to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050

[7] https://www.fitchratings.com/research/banks/climate-stress-tests-to-be-mainstream-for-banks-insurers-15-03-2021

[8] https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/feds-powell-signals-hes-open-using-climate-stress-scenarios-2021-07-15/

[9] The Network for Greening the Financial System is a network of 83 central banks and financial supervisors that aims to accelerate the scaling up of green finance and develop recommendations for central banks' role for climate change

[10] The list of banks and insurers is as follows: Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group, Nationwide Building Society, NatWest Group, Santander UK, Standard Chartered, Aviva, Legal & General, M&G, Phoenix, Scottish Widows, AIG (UK entities only), Allianz Holdings plc (UK entities only), Aviva, AXA (UK entities only), Direct Line, RSA (UK entities only), Society of Lloyd’s (Ten selected Syndicates)

[11] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/stress-testing/2021/key-elements-2021-biennial-exploratory-scenario-financial-risks-climate-change

[12] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/stress-testing/2021/key-elements-2021-biennial-exploratory-scenario-financial-risks-climate-change

[13] https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insights/banking/climate-change-risk-banks